Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund (VSJF) proudly announces RioNadi as the peer-selected winner of its DeltaClimeVT Energy 2025 business accelerator, following a four-month intensive program designed to fast-track energy innovation in Vermont. In addition to the $25,000 award, RioNadi secured a pilot project with Burlington Electric Department (BED) to test its electric vehicle monitoring and payment system technologies.

VBSR News

At VBSR, we believe in the power of sharing insights, achievements and perspectives. Here, we bring you news that not only includes VBSR-generated communications but also exciting news items – and inspiration – shared by our valued members. This space is a dynamic showcase of sustainable business practices, corporate responsibility initiatives and the latest updates from the Vermont business community.

Would you like a version of this page and much more delivered to your inbox? Sign up for the VBSR Newsletter and you’ll get inspirational snapshots and actionable updates on a bi-weekly basis!

A group of hemp producers and craft brewers are coming together to establish Vermont as a leading producer of non-alcoholic hemp-infused beverages.

Sodexo’s Vermont First Program has received national recognition for its leadership in local food sourcing, earning the Gold Award for Sustainable Procurement from the National Association of College and University Food Services (NACUFS) as part of the 2025 Sustainability Awards.

In this moment, when our democracy faces unprecedented challenges and uncertainty seems to be the only constant, our work together becomes even more crucial – let’s commit to finding creative inspiration together in the many “unexpecteds” this moment provides.

VBSR’s efforts during the 2025 Vermont Legislative Session have come to a close and we have much to celebrate – while still having more to accomplish when the State House reconvenes in January 2026.

The sold-out 35th Annual Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility (VBSR) Conference, “All Together Now”, was held on May 8, 2025, at Hula, the award-winning lakeside coworking and innovation campus in Burlington. Participants explored ways to meet this moment for business with courage, solidarity, and solutions.

35th Annual VBSR Conference Set for May 8th at Hula; Meeting this moment for business with courage, solidarity, and solutions – The 35th Annual Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility (VBSR) Conference, “All Together Now”, will be held May 8th at VBSR Champion Member Hula in Burlington.

VBSR, the statewide, nonprofit business association with a mission to leverage the power of business for positive social and environmental impact, has named Chelsea Bardot Lewis the organization’s new executive director. Bardot Lewis will take leadership of the organization on June 1.

VBSR members met with key Vermont policymakers during our annual lobby day, March 11, 2025, addressing the impacts of climate change on Vermont’s businesses and economy.

In these times of uncertainty, we can be more powerful together, and we want to include YOU in our movement - leaning into our values and leading our state toward an equitable, sustainable, and prosperous future through advocacy, education, networking, and thought leadership. Come be a part of what we are building.

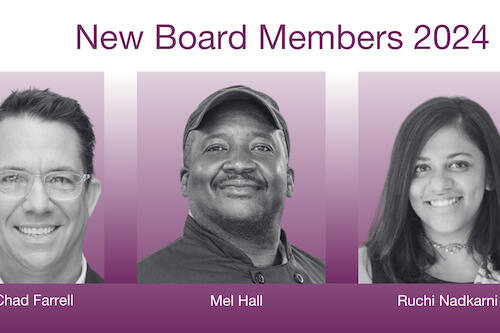

Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility, the statewide, nonprofit business association with a mission to leverage the power of business for positive social and environmental impact, is pleased to welcome three new members to the organization’s Board of Directors: Rooney Castle of Rhino Foods, Ashley Laporte of Burton, and Eliza Leeper of Vermont Creamery.

Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility (VBSR) is pleased to announce that Ed Richters has joined the organization as Finance and Operations Manager. In this role, Richters supports VBSR’s efforts by advancing the organization’s mission through managing its financial and operations systems.

Efficiency Vermont has increased offers for businesses replacing equipment damaged by the 2023 and 2024 summer flooding.

VBSR announced today that Roxanne Vought will depart her post as the organization’s seventh executive director on May 30, 2025. After a total of 10 years with VBSR in various roles, she is leaving to support an aging parent.

VBSR recognized Vermont State Senator Kesha Ram Hinsdale from Shelburne (Chittenden-Southeast District) with their 2024 VBSR Legislator of the Year Award, honoring her during the 2024 VBSR Legislative Breakfast on Wednesday, December 11 when VBSR also announced its 2025 Advocacy Agenda.

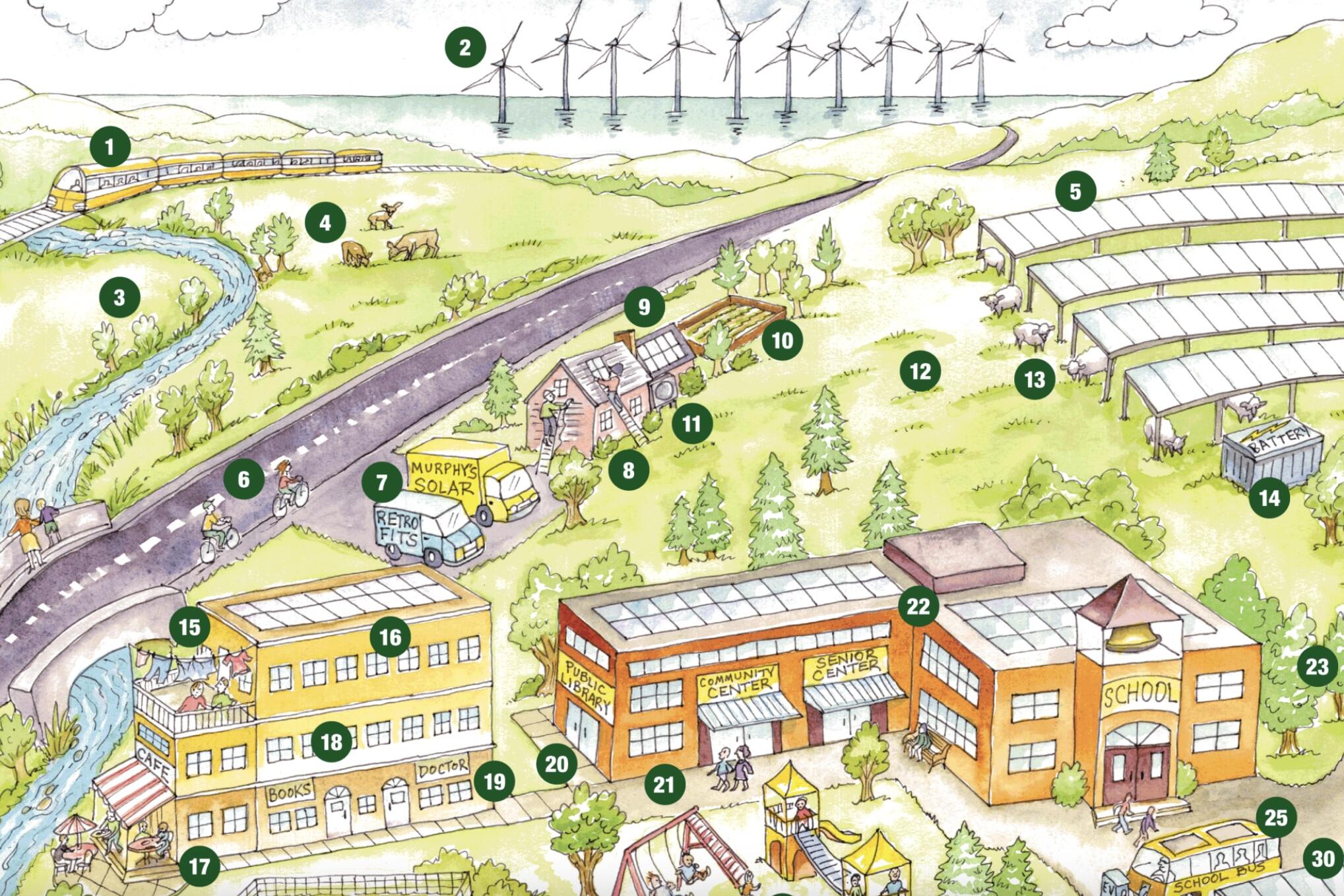

VEEP's new poster includes a beautiful illustration by local artist Sarah-Lee Terrat that shows a community that has done an amazing array of things to prepare itself for a changing climate.

WheelPad was thrilled to be selected as one of the twelve Southern Vermont CEDS 2024 Vital Projects by a volunteer committee of local leaders across the region.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Children's Literacy Foundation, Hula, Northeast Delta Dental, Northfield Savings Bank, UVM, Union Mutual, VFCU, Vermont Works for Women, and more!

Burlington, VT – December 2, 2024 – Cultivate, a Vermont-based, woman-owned public relations agency specializing in media relations, social media, and influencer partnerships, announces the launch of its Roots & Blossoms Fund, a new grant initiative designed to support artistic and cultural programming for Vermont youth.

VBSR has recognized Vermont State Senator Kesha Ram Hinsdale from Shelburne (Chittenden-Southeast District) with their 2024 VBSR Legislator of the Year Award. Senator Ram Hinsdale will be honored as VBSR’s Legislator of the Year during the 2024 VBSR Legislative Breakfast on Wednesday, December 11 when VBSR will also announce its 2025 Advocacy Agenda.

Building houses, community, and solutions to climate change one straw bale at a time.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Middlebury College, Encore Renewable Energy, Green Mountain Power, Beta Technologies, Caledonia Spirits, Darn Tough Vermont, DeltaClimeVT, and more!

On October 22, Peter Plumeau of Reframe Lab presented in the National Adaptation Forum’s "Moving Towards Preparedness for Extreme Weather Events" webinar series.

MONTPELIER, VT – The DeltaClimeVT climate economy business accelerator is seeking innovative start-up and seed stage ventures offering innovative products and services aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing resilience in an effort to help Vermont meet its climate goals.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Vermont Works for Women, Capstone Community Action, Energy Action Network, Generator Makerspace, Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, and more!

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Cabot Creamery Cooperative, Barr Hill Gin & Caledonia Spirits, Brattleboro Savings & Loan, CATMA, Lawson's Finest Liquids, and more!

News Item Description: Do you know a high school student who wants to make a difference on climate change? Registration is now open for VEEP's Youth Climate Leaders Academy.

The founder of WheelPad L3C, Lineberger and her team create fully accessible housing for veterans, seniors, and people with spinal cord injuries or debilitating illnesses.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: The Landmark Trust USA, Casella Waste Systems, Evernorth, Green Mountain Club, VCET, and more!

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Adventure Dinner, Cabot Creamery Co-operative, VSJF, Cabot Creamery Co-operative, VSJF, and more!

Explore the latest from VBSR members:UVM Medical Center, AO Glass, Ben & Jerry's, Hotel Vermont, Champlain Housing Trust, and more!

Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility (VBSR), the statewide, nonprofit business association with a mission to leverage the power of business for positive social and environmental impact, has announced the 2024 recipients for three awards honoring Vermont leaders in social equity, environmental responsibility, and sustainable economic development. The date and location for the 23rd Annual VBSR Awards Ceremony and Dinner have been set for Thursday, October 10, 5-8:30 p.m., at The Barn at Smugglers’ Notch, Jeffersonville.

Business Sense is a no-fluff source of information that gets right to the heart of what small business owners need: essential tools and relevant resources to help their businesses grow.

Explore the latest from VBSR members:UVM Medical Center, Chroma Technology, ECHO / Leahy Center for Lake Champlain, Green Mountain Club, and more!

VBSR Welcomes Johanna de Graffenreid as Public Policy Manager: In this role, de Graffenreid supports VBSR’s efforts to advance the organization’s policy goals, working closely with VBSR members. de Graffenreid has nearly 20 years of experience as a community organizer, advocate, lobbyist, campaign director, and trainer – including with businesses and economic development entities.

VBSR Announces Free Climate Resilience Program for Small Businesses: second cohort of ClimateReadyVT launches; the free program is helping small businesses in Vermont adapt to our changing climate and prepare for climate-related business disruptions.

Explore the latest from VBSR members:Champlain Housing Trust, King Arthur Baking Company, Brattleboro Savings and Loan, National Life Group, Lawson's Finest Liquids, and more!

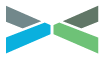

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Green Mountain Transit, BlueCross BlueShield of Vermont, King Street Center, Pride Center of Vermont, Cabot Creamery Cooperative, and more!

VBSR has announced that Encore Renewable Energy has joined the organization’s core group of Champion Members.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Darn Tough Vermont, Casella Waste Systems, Lawson's Finest Liquids, Evernorth, Champlain Housing Trust, Vermont Housing Finance Agency, and more.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Local Motion, Casella, UVM, Green Lantern Solar, Green Mountain Power, Vermont Electric Cooperative, Hula, Darn Tough Vermont, Vermont Foodbank, Leahy Center for Lake Champlain and more.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Vermont Arts Council, VSECU/NEFCU, SunCommon, Vermont Professionals of Color Network, EverNorth, Adventure Dinner, Vermont Energy Education Program, Solaflect Energy, and more.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: BCBSVT Mountain Days, CATMA bikeshare, Gardener's Supply Company new location, VEOC conference, and a Vermont marketplace in NYC.

34th Annual VBSR Conference: Photos and Recap – Explore photos and highlights of the sold-out 34th Annual VBSR Conference where participants explored the transformative power of nature and technology, agency, and joy.

Vermont Architect Secures CDFI Funding to Build Sustainable Affordable Housing after Pandemic and 2023 Flood: With support from Flexible Capital Fund, L3C, Up End This built five accessory dwelling units (ADUs) which were purchased by the City of Burlington, VT, as part of the community they built for their unsheltered population. These units were built with cold winters in mind- they are highly insulated and energy efficient.

VBSR business and nonprofit leaders, policymakers, students, and inspired individuals will gather for a full-day event that will include a keynote address by Ferene Paris, six timely sessions, two innovation labs focused on the leading edge of social and environmental impact, and ample opportunities for networking and meeting exhibitors.

Explore the latest from VBSR members: Beta Technologies advances green aviation, Burlington's new park project nears completion, ClimateReadyVT aids small businesses, UVM pushes for forest protection, NOFA-VT advocates in DC and local nominees for the James Beard Awards.

Learn about the four new board members at VBSR and how their unique perspectives will drive social and environmental change in Vermont.

Explore how VBSR members like Up End This and Lawson's Finest Liquids are making strides in affordable housing and sustainability. Learn about their latest projects and partnerships in our March roundup.

The Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund (VSJF) announces the selection of the Energy 2024 cohort of the Vermont-based DeltaClimeVT climate economy business accelerator.

Vermont’s Businesses Call for the Passage of Flood Recovery Assistance Program; 200+ Business Signatures Urge Legislators to BACK THE FRAP

Discover how Vermont's Baby Bonds program proposes to invest in the state's children, offering a solid foundation for wealth-building and a brighter, more equitable future.

Leadership from Vermont Businesses for Social Responsibility (VBSR), Vermont Public Interest Research Group (VPIRG), Seventh Generation, SunCommon, and more called for bold climate action this legislative session at the State House in Montpelier.

Learn about the collaboration efforts to minimize food waste and support local communities by repurposing surplus farm produce for food shelves and senior meal programs.

Explore the latest strides in sustainability and social responsibility from VBSR members in Vermont. Discover how local businesses and organizations are leading change in January 2024.

Discover Vermont's strategic plan for food security by 2035, developed with input from over 600 Vermonters. Learn about the initiatives for sustainable, equitable access to nutritious food for all.

The Governor’s Institutes of Vermont (GIV) is now accepting applications for the 2024 offerings of its residential summer programs.

Get inspired by the collective efforts of VBSR members in areas like education, organic farming, and social responsibility. From UVM's job fair to advocacy for improved childcare, see how we're making a difference.

Discover how a VBSR member agency is aiding youth with intellectual disabilities and autism in achieving their career goals through strategic partnerships and support services.

High 5 Adventure Learning Center announces Jennifer Ottinger as its new Executive Director, marking a new chapter in leadership and commitment to experiential learning.

VBSR welcomes Jeremy Gerber as its new Membership and Development Manager, bringing a diverse skill set in nonprofit development and digital marketing to the team.

Discover how VBSR members are making strides in sustainability, from unionizing efforts to climate action awards and advancements

Matthew Bushey steps into the role of Managing Principal at TruexCullins Architecture + Interior Design, bringing a fresh vision for sustainable design and innovation.

From Efficiency Vermont’s flood recovery rebates to the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund’s energy initiative, explore how VBSR members are driving positive change and innovation in their communities.

Learn how Salvation Farms is revolutionizing school menus with locally-sourced, surplus crop-based frozen foods, backed by the New England Food Vision Prize for their impactful work.

Explore how VBSR members like King Arthur Baking and Lake Champlain Chocolates are addressing sustainability, workforce challenges and more.

Celebrating Emilie Kornheiser's recognition as VBSR's 2023 Legislator of the Year for her impactful work in supporting socially responsible business and policy in Vermont.

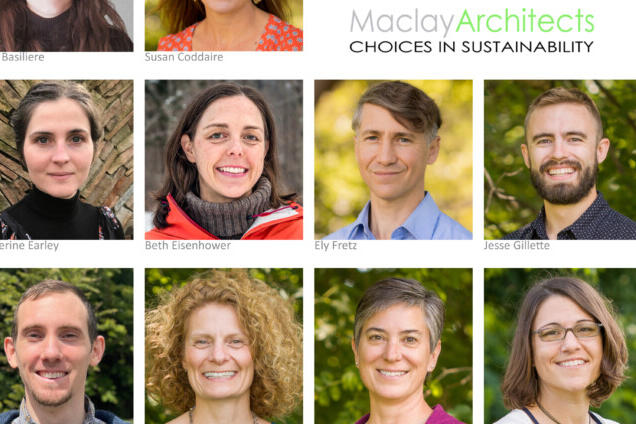

Beginning January 2024, Maclay Architects joins forces with Vermont Integrated Architecture, ushering in a groundbreaking chapter in sustainable design. Explore the future of architecture with VIA Maclay Studio.

Explore lessons from Janice St. Onge's 10 years of impact investing in rural communities by the Flexible Capital Fund, focusing on sustainable food, forestry and climate solutions.

Uncover how VBSR members are driving sustainability forward through innovative projects like solar energy adoption, waste reduction, and supporting local communities.

Explore the latest sustainable business practices and community impacts by VBSR members in Vermont, including renewable energy initiatives, innovative recycling programs and more.

DeltaClimeVT's Climate Economy Accelerator is on the lookout for entrepreneurs with groundbreaking energy innovations. Join our 2024 cohort to drive Vermont's renewable goals forward.

Delight in Vermont's rich agricultural heritage and community values at the 16th Annual Taste of Vermont in D.C., with Senator Bernie Sanders, showcasing more than 30 leading brands.

Engage in VBSR's comprehensive JEDI Spring 2024 Training Series. Enhance your understanding of Unconscious Bias, Microaggressions, Class & Classism, and Power Dynamics with expert facilitators.

Dozens of VBSR CEOs and business leaders gathered in Montpelier on Thursday, March 16, to deliver a decisive call for climate action.

In the wake of challenging SCOTUS decisions, VBSR advocates for Vermont to lead with a values-led approach, emphasizing the impact on public health, human rights and the environment.